Sophia Dunn-Walker on Vision, Rebellion, and the Art of Staying Dangerous

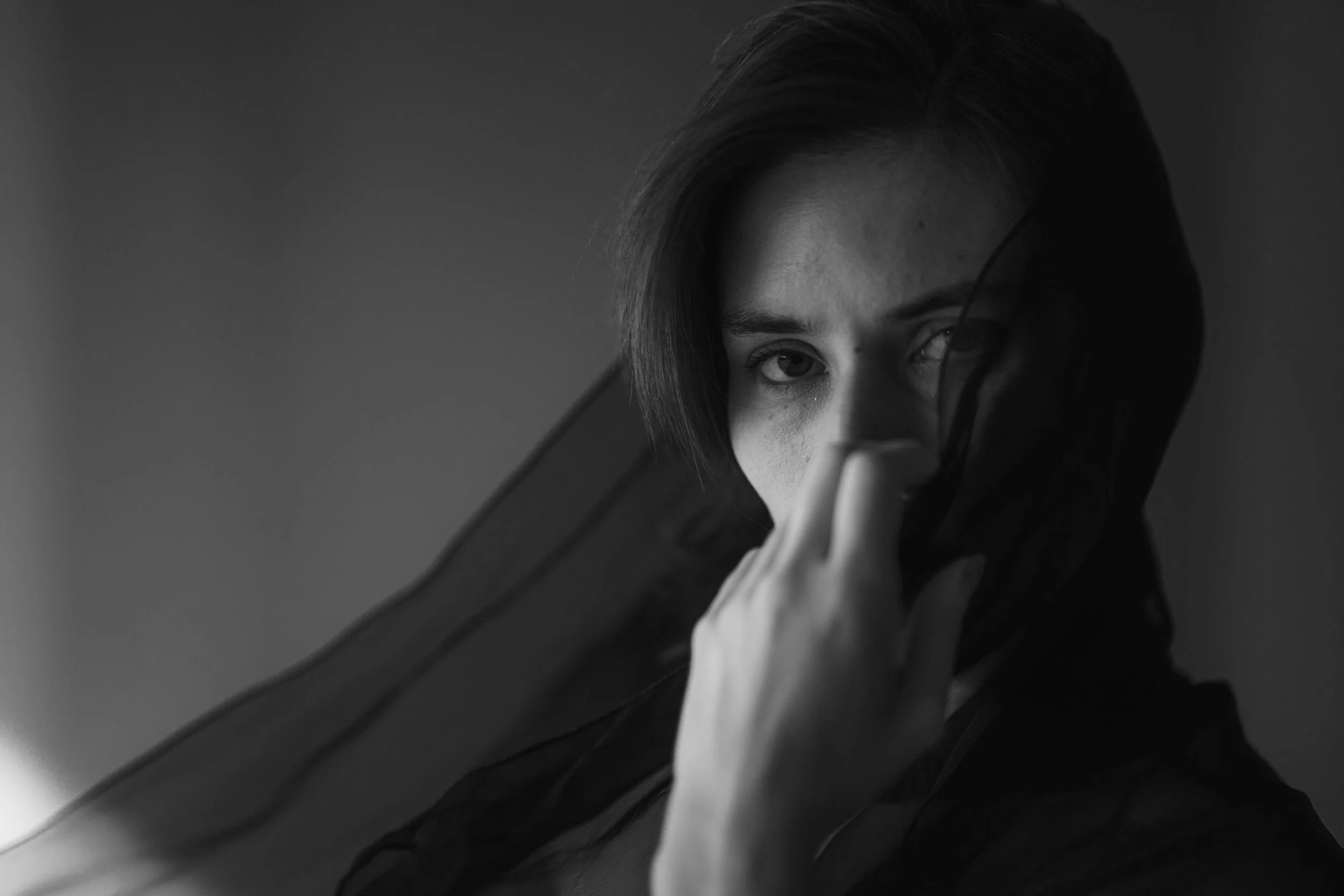

Photo by Ben Staley

French-American filmmaker Sophia Dunn-Walker isn’t interested in playing it safe. Formerly a punk musician who briefly performed with the French band Litige and fronted her own project, Avenir Aveugle, Dunn-Walker now brings that same raw defiance to her work behind the camera. Legally blind and fiercely independent, Dunn-Walker’s perspective bridges art house and action, high concept and underground authenticity. In this conversation, she talks about instinct, feminism, and why real edge means slowing down in a world obsessed with speed.

You started in music, performing in the punk band Litige and fronting Avenir Aveugle. How did this experience shape your sense of rhythm and tension in the arts?

I was very briefly a part of Litige. They have a raw energy about them and had some mainstream access but were fairly underground, so it taught me a lot about resilience and finding inherent value in what you do as an artist while celebrating bigger forms of success. Being in a band can be really emotional, especially when you’re young. I was in another punk band as well, and it was a lot of fun and a really great cathartic form of expression. But there’s also a lot of tension. Bands are kind of notorious for breaking up and getting back together, and it can bring out people’s biggest emotions.

Courtesy of Sophia Dunn-Walker

Do you see any parallels between punk and filmmaking?

I try to embody the energy of having been in a band into filmmaking, because I think there’s a common mentality in filmmaking that you have to get money before you get an actor, or you have to get famous before you can be successful, or you have to have a lot of money. And there’s truth to that to an extent, but being in a band teaches you how to create and just get started and not overthink it, which I think is really important to being an artist.

You’ve talked about trusting instinct over formula. Where does your instinct come from? Your musical past, your French roots, or something else?

I think everyone is born with really great instincts, and I think most children are creative geniuses. I do think people are encouraged to get away from their instincts. Instinct is something that you’re born with. How does this influence the way I frame a story? The most successful projects I did were underprepared, actually, and the projects that I’ve done that were the least successful were over-manicured and over-formulaic. I’m really drawn to very raw, visceral narratives that champion and platform women.

There’s a strong French connection across your projects. What does French culture bring to your storytelling?

It’s just different. I think France gets overly romanticized by American artists as being this kind of mecca for artists, and I’m cautious to not overly romanticize it because, at the end of the day, it’s still a patriarchal country with a lot of problems, where women are blackballed and given limited forms of power, and there’s a lot of sexual harassment and sexual violence there. I want to say that because it really frustrates me when male filmmakers or male musicians romanticize France, and it’s just not the reality for women there. But I think the French do value art for the sake of art more. There’s a longer history, but also a richer underground. The balance or dichotomy of underground and prestige is really dope. I used to go to the opera all the time because it’s more accessible there.

You’re directing a new action film. Can you tell us more about the project?

Yes. It’s been a long time in the making. We started filming about two years ago, and we’re using footage to be memory sequences. I’m working closely with a stuntwoman named Lauriane Rouault. She’s worked on a lot of Marvel films and major French action films. She was just in The Odyssey. I’m really interested in fierce, fast-paced entertainment, but I’m also interested in seeing female physicality on screen, because a lot of female physicality has been seen through the male gaze, even if it’s supposedly empowering. Men tend to fetishize the female experience. Women are either porn stars or these untouchable action badasses, and I think the reality is far more nuanced. I want to capture something larger-than-life and visceral while still being truthful to what the female experience is in the world.

What do you want people to feel when they see your work?

I like being funny and fun and uplifting, but then there are a couple of gut punches in there. I want to be emotionally raw and truthful, and I want people to feel very big, deep emotions. I want people to feel a sense of relief. For example, I saw Cabaret for the first time on stage recently and expected it to be cheesy or dated, but at the end of it I remembered weeping. The story was told so effectively. It was validating to see as an artist because I think they did a fantastic job with it at the Guthrie.

How do you define edge today, and how do you keep that spirit alive as your career expands?

That’s a great question, because to be honest, I would love to get to the point where I have the ability to “sell out,” but I do see a pattern where an artist’s first couple of projects are their best, and then they lose their sense of self. Edge today means not buying into fast culture—fast content, fast fashion. You have to have depth to create something that sticks. I like having an edge, but I don’t want to be provocative for the sake of being provocative. If everything is provocative, then nothing is. We want more sex, more money, more exposure, and more fame. Society has become so gluttonous and hedonistic that those things aren’t taboo or interesting anymore. So, you have to find something deeper and more emotional.

How does your background in punk influence how you run a film set?

It doesn’t. That’s a funny question, because I wish it did more, but it’s almost the opposite. Running a film set means I have to be the adult in the room, whether I like it or not. When I work with actors, I like to explore their emotions in a more experimental way, and I’m very collaborative with artists. You can see a bit of punk influence in the stories I tell, but when I’m running a set, I have to become a different type of person.

When you think about your creative identity, do you feel more connected to France or the U.S.?

I like that I have access to both. I actually left France because I felt there wasn’t enough experimentation or lawlessness there. It felt like the industry was smaller, and I wanted a place where I could let loose. In the States, if you need an eight-foot-tall puppet made for you tomorrow, you could get that. If you needed a guy in a BDSM dog mask, you could find 20 people within an hour. You can get belly dancers, contortionists—anything. There’s just more here, which has a lot of benefits. But I do think the French have a greater appreciation for art as a whole.

How does being legally blind affect your creative process, both in limitation and freedom?

My disability is peculiar because it’s fairly mild, but it influences the way people treat me and understand my capacities, which is already tricky as a woman. There’s a lot of virgin-whore dichotomy for women, and women are easily infantilized. With a disability on top of that, it can be hard to be taken seriously at all. Film is a boys’ club. I’ve been in environments where women have multiple albums or feature films and are barely treated with respect, and then guys making half-baked indie films are all just kind of jerking each other off. Men simp over each other. Men are socially conditioned to value each other more as intellectuals and artists. As a woman, you have to be twice as good to be looked at at all. With a disability, it’s tricky because you don’t want to seem incompetent, but sometimes you do need accommodation and help.

Photo by Ben Staley

How do you decide when a project is worth pursuing?

If I’ve had the idea and it’s been itching at me for a long time, then it has to get made. My advice to any artist would be to just start making one of your ideas. Some of them you’ll be able to make, and some of them you won’t, but you just have to make as much work as you possibly can. I wish I had done that earlier.

Do you see music and film as separate languages or part of the same expression?

They’re pretty different. There are more steps to film. It’s more political. Getting visibility as a musical artist is political, but making a film is inherently political because you need a crew. Even a small shoot involves three people, usually closer to 25, and on a bigger set, you can have hundreds. But the finished products can be part of the same expression. It’s just harder to make a film.

What kind of stories feel dangerous enough to be interesting to you?

Unfortunately, I wouldn’t have said this a few years ago, but in Trump’s America, any type of feminism is dangerous. Women telling women’s stories is controversial. I’m sick of seeing men directing so-called feminist films because I don’t think they’re doing a good job. They’re painting women as caricatures and cartoons. I’m tired of it.

How do you keep your projects inclusive without softening their edge?

Inclusivity culture can feel mommy-ish. Sometimes it feels like a PTA meeting because the so-called moms make it about themselves more than about the children who are actually suffering. But inclusivity is inherently good for storytelling because different perspectives add richness, depth, and edge to a project. If people are truly in touch with the pain they’ve experienced as outsiders, that adds dimension. It’s inherently valuable.

What makes something feel punk to you now, not in genre but in spirit?

I’m paradoxical. I want to be rich. I want to be capitalistically successful. I like luxury. But there’s something in me that will always be drawn to the underground and the DIY aspect. There’s a part of me that wants to live off-grid and a part that hates the system. Society is getting darker for women. It’s becoming less compassionate. I straddle the line of wanting to conquer the world and also not wanting to engage in it at all.

What do you still want to rebel against in the industry?

I know powerful people whom I admire and want to be more like, but there are a lot of systems that are stale and uninteresting. Even independent film feels formulaic right now. I want to make something truly original. I only want to make something based on instinct. I’m grateful I didn’t go to film school. Being an artist should be inherently rebellious. You should not only challenge the system but also challenge your friends and everyone you meet. I think it’s good to be antagonistic. You should always be a skeptic and an individual, because that makes the collective better.